Custom Elements or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Web Components

If you’re reading this and you’re a developer on the web, you’ve probably had to write front end code at some point. You’ve likely had to make some custom pages as well as a date picker, image carousel, or stylized button. As a front end developer, you’ve probably had to make these kinds of components over and over again. And if you need to create that stylized button, for example, you can find more than 1,300 custom button libraries to use on NPM!

Most of these buttons are specific to a framework such as Angular, Vue, or React, which is fine since those are the most popular frameworks on the web right now. But what happens when you find a button (or another component) that isn’t compatible with your framework?

My typical response is to move onto the next library until I find something I like. However, some libraries, like Ionic, are just too good to be ignored. The problem is that for the longest time, Ionic only supported Angular, so if you used any other framework, you’d have to use an unofficial wrapper library.

There should be a framework-agnostic solution!

There are three framework-agnostic ways we can handle this.

The CSS Approach

You can use a CSS library. A great example is Bootstrap.

<html>

<head>

<link href="https://stackpath.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/4.2.1/css/bootstrap.min.css">

</head>

<body>

<button type="button" class="btn btn-primary">Primary</button>

<button type="button" class="btn btn-secondary">Secondary</button>

<button type="button" class="btn btn-success">Success</button>

<button type="button" class="btn btn-danger">Danger</button>

<button type="button" class="btn btn-warning">Warning</button>

<button type="button" class="btn btn-info">Info</button>

<button type="button" class="btn btn-light">Light</button>

<button type="button" class="btn btn-dark">Dark</button>

<button type="button" class="btn btn-link">Link</button>

<script src="https://code.jquery.com/jquery-3.3.1.slim.min.js"></script>

<script src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/popper.js/1.14.6/umd/popper.min.js"></script>

<script src="https://stackpath.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/4.2.1/js/bootstrap.min.js"></script>

</body>

</html>As shown above, you import Bootstrap via a CDN in the <head>, have a few different buttons in the <body>, and finally, import a few of the necessary JavaScript libraries toward the bottom of the <body>.

The end result is lovely, but it requires a few things:

- For Bootstrap to function properly, you don’t just need to bring in the CSS required to stylize the components and a JavaScript file for certain components’ to have custom behavior. There’s nothing inherently wrong with the custom JavaScript logic, but you end up requiring JavaScript libraries outside of Bootstrap’s JavaScript, such as JQuery and Popper. This is added bloat that your application must load to run.

- You may end up with some gorgeous buttons, but do you remember all of the classes Bootstrap uses? The only classes I know well are the grid-related classes. For everything else, I go to W3Schools (although I hate to admit it). 😅

Ok, so this is a solution, but it may not be the best solution.

The JavaScript Approach

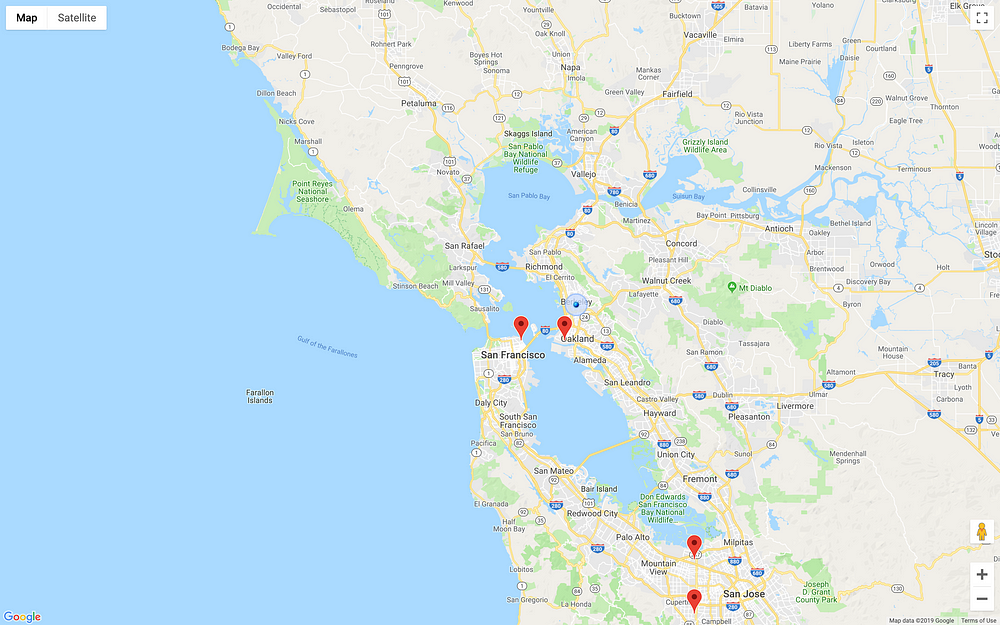

A different solution is to use pure JavaScript, which you see in libraries like Google Maps.

<html>

<head>

<script src="https://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/js?callback=initMap" async defer></script>

</head>

<body>

<div id="map" style="height: 100vh; width: 100vw;"></div>

<script>

var map;

function initMap() {

map = new google.maps.Map(document.getElementById('map'), {

center: { lat: -34.397, lng: 150.644 },

zoom: 8

});

}

</script>

</body>

</html>With this solution, you include the JavaScript library in the <head> of your page. Then, you can use a DOM element to display the component.

This solution ends up being neater, and as a nerd, it just feels good. Even so, some problems arise:

- If you need a JavaScript-based library like Google Maps with frameworks like Angular and React, you’ll probably need a wrapper library to use it. Why? Modern frameworks try to extract access to the DOM for their rendering engines, and direct DOM manipulation is discouraged.

- Worse yet, JavaScript-based libraries like this one don’t play well with server-side rendering.

Both of these solutions are, well… 🤮

So what’s a better solution?

The Web Components Approach

From https://www.webcomponents.org:

Web components are a set of web platform APIs that allow you to create new custom, reusable, encapsulated HTML tags to use in web pages and web apps. Custom components and widgets build on the Web Component standards, will work across modern browsers, and can be used with any JavaScript library or framework that works with HTML.

What are these (magical) specs? There are 4: Custom Elements, HTML Templates, Shadow DOM, and HTML Imports (DEPRECATED). Although all of these specs are important, Custom Elements is the one we’re interested in for our purposes (and the one that causes the most confusion about what web components are).

The Custom Elements spec lays out how to create new HTML tags as well as extend existing HTML tags. By extending the built-in HTMLElement class, you can build your own reusable DOM elements using just JavaScript, HTML, and CSS. You end up with modular code that is easy to reuse in your applications and requires less code to write. No more needing to remember 500 different class names!

If you can’t imagine why you’d want to create Custom Elements, let me ask…

- Do you have to remake the same button in Vue that you made 3 weeks ago when your company was a React shop? And will you switch frameworks again next month?

- How about if you want to create a component library, like Ionic, that can be used with any framework or no framework at all!?

- What happens when you work at a large company, where each department uses a different framework for its product, and the company decides to update the brand style guide? Does every team have to make the same buttons, navbars, and inputs?

- What if you 😍 the 90s and want to bring back the

<blink>tag?

The answer: create a Custom Element!

// ES6 Class That Extends HTMLElement

class HelloWorld extends HTMLElement {

// We Can Have Attributes And Listen To Changes

static observedAttributes = [‘name’];

attributeChangesCallback(key, oldVal, newVal) {}

// We Can Get And Set Properties

set name(val) {}

get name() {}

// We Have Lifecycle Hooks

connectedCallBack(){}

disconnectedCallBack(){}

// We Can Also Dispatch Events!!!!

onClick() {

this.dispatchEvent(new CustomEvent(‘nameChange’, {}));

}

}

// Register to the Browser from `customElements` API

customElements.define(‘hello-world’, HelloWorld);By extending the HTML element, you can define your Custom Element and do most things that you’d expect from a modern framework:

- Define attributes for your element, which are values you pass to an element through the HTML tag, like an id or class. You can also trigger a callback based on changes to the attribute. Keep in mind that you can only pass in strings.

- Your element has setters and getters for its properties, and you can pass complex data types (non-strings) to your element.

- Use life cycle hooks for element creation and destruction.

- Dispatch events based on interaction and other triggers in the element.

When all is done and you’ve built your beautiful element, you can register it by passing the selector you want to use and then the class you created into the define method.

Custom Elements in Action

Below is an example of a Custom Element in use: the long-deprecated <blink> tag. The logic for the element and the code that registers it to the DOM are bundled into a JavaScript file, which is loaded from a CDN in the <head>. Then, in our <body>, the <blink> tag is used like any other HTML element. If you don’t believe that this is a real Custom Element, I invite you toinspect the TS file. The <blink> tag is a registered element and can be created with simple DOM manipulation.

If you’re interested in learning more about Custom Elements, I recommend these resources:

- https://www.webcomponents.org/introduction

- https://polymer-library.polymer-project.org/3.0/docs/first-element/intro

- https://dev.to/bennypowers/lets-build-web-components-part-1-the-standards-3e85

And if you’re interested in the <blink> tag, you can find my code on GitHub or a packaged version of the library on NPM.

To keep up with everything I’m doing, follow me on Twitter. If you’re thinking, “Show me the code!” you can find me on GitHub.